This is paragraph text. Click it or hit the Manage Text button to change the font, color, size, format, and more. To set up site-wide paragraph and title styles, go to Site Theme.

How people live and work has changed dramatically over the past decades as technology is now seamlessly integrated into our daily lives. From television remotes, computers, GPS systems, doorbell cameras, and the like, we have all moved towards dependence on technology. For many individuals with disabilities, the use of assistive technology (AT) to participate in social activities and activities of daily living (like bathing, eating, dressing, communicating, and moving from place to place) has also increased. In 1998, Congress passed the Assistive Technology Act (P.L. 105-394), which made provisions for persons with developmental or acquired disabilities to access AT that can effectively decrease barriers found in everyday life while increasing access to and improving the quality of life.

In 2004, Congress amended the Assistive Technology Act (P.L. 108-364), noting that 54 million Americans had disabilities, with half of those individuals living with a severe disability. Federal law describes AT as any item that can maintain or improve the functional capabilities of a person with a disability.

As technology has become more sophisticated, so too have the AT tools that can be used to improve the lives of those with disabilities. The best AT tools and strategies are determined by the needs and goals of the individual, in conjunction with family members and care providers. The population of individuals needing AT is diverse and covers a wide range of disabilities. For some, the needs may be AT that has been used for decades, like eyeglasses, hearing aids, and communication boards. Others may need sophisticated tools such as speech-generating devices or equipment to assist positioning and mobility. Assessing individual needs is key to finding the right AT. To the greatest extent possible, every individual needing AT should participate in establishing and implementing an AT plan. There are multiple considerations to address in establishing an AT plan, including what barriers to independence need to be overcome or removed, what supports are necessary for functional progress, how can communication be assisted to increase options and opportunities for social interaction and participation, and what plans can be established for adapting activities and materials needed to encourage active engagement. As much as possible, the individual should help assess what is working or not working in their AT plan and help the AT specialist to generate potential solutions to problems that arise. Over time, plans will need to be updated and changed to correspond with changes in current levels of functioning. Therefore, AT needs and tools should be reassessed regularly to address current goals. Benefits of Assistive Technology Individuals with significant brain injuries often benefit from AT. It is essential to determine specific areas of need that may benefit from AT, including physical, sensory, cognitive, communication, academic, environmental control, social competence, vocational, and recreational. The person experiencing brain injury, their family, therapists, educators, rehabilitation engineers, physicians, and caretakers all may play a part in determining AT solutions. Finding therapists and caretakers knowledgeable about the implementation of AT and who can work on both short and long-term goals holds the most promise for reintegrating those with disabilities into purposeful life activities. Certified AT specialists can be found through the following link: https://www.resna.org/

The process of obtaining an initial AT evaluation and accessing AT equipment or devices is not always easy. It may help to contact your state’s brain injury association and check their website (a state-by Support The Dan Lewis Foundation when you shop at smile.amazon. Thank you to our amazing donors! state listing of brain injury associations is included in this newsletter). Additionally, every state has an AT project that is funded as part of the federal guidelines established in 1998 and can be accessed through: https:// askjan.org/concerns/State-Assistive-Technology-Projects.cfm

A child’s school team may have an AT specialist, or there may be a school district-wide AT specialist who should be called upon. For any student with special needs (including students with severe brain injuries), AT needs should be considered in forming an Individualized Educational Plan (IEP) or 504 plan. For an adult, a care coordinator may help find resources to meet AT needs. Alternatively, the individual’s medical team may be helpful, particularly occupational and physical therapists. Funding sources for equipment and devices vary from state to state, given that different agencies may bear responsibility for AT in different states. Again, it may be best to contact your state’s brain injury association to find an advocate, “system navigator,” or referral specialist who can steer you toward funding sources for AT. It is vital for family members or other advocates for the individual with a severe brain injury to be assertive in identifying and procuring the AT resources that are needed.

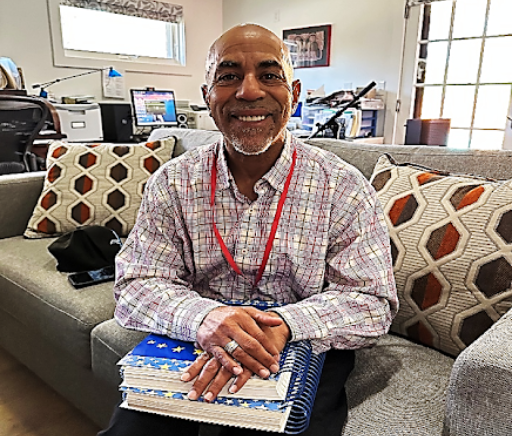

Kristen Gray M.A., ECE, ATP is an assistive technology specialist