From ancient times to modern times, making music has been a quintessential human capacity—a powerful channel for communication, expression, and communality. The ancient Greek philosopher, Plato, wrote, “Music gives a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, and life to everything.” The modern composer, Leonard Bernstein, said, “Music can name the unnamable and communicate the unknowable.” What benefits might music have for persons recovering from brain injury?

Kimberly Sena Moore, a boardcertified music therapist and neurologic music therapist in private practice, has written, “When used properly, music can be an incredibly powerful treatment tool. And not just because it’s fun, relaxing, and motivating, but because music has a profound impact on our brains and our bodies.” Moore lists her top brainbased reasons why music works in therapy .

» Music is a core function of our brain.

» We physiologically match (entrain to) to rhythmic beats.

» Children (even infants) respond readily to music.

» Music taps into our emotions. »Music helps improve our attention skills.

» Music uses shared neural circuits with speech.

» Music enhances learning.

» Music taps into our memories.

» Music is predictable, structured, and organized.

» Music is a social experience.

» Music is non-invasive, safe, and motivating.

Several years ago, Kristi Staniszewski, The Therapeutic Power of Music RPT, along with a neurologic music therapist, Sarah Thompson, initiated music and movement groups through the Brain Injury Alliance of Colorado.

Kristi notes, “There is something magical about music and how it influences our thoughts and feelings. Music can find its way into parts of the brain that may not be accessible via other experiences. For instance, a person who cannot speak due to aphasia may hear a familiar song and be able to sing the words.”

Kristi adds, “Music is fun. It can make exercising or remembering or any of the ‘tasks’ we are asking members of the group to work on…fun. It doesn’t feel like work; it feels like fun.” Her comments raised a thought: there must be a reason we call it “playing music” rather than “working music.” Music is a wonderful vehicle for bringing people together; people from different classes and cultures can enjoy a musical experience together. In this group, the facilitators put a lot of emphasis on the group members communicating with each other. In Kristi’s words, “Whether it’s through a song or a memory or about something they learn about each other, the communication among the group members is very important. I think people with brain injuries can tend to get isolated and feel they are alone with their issues. So, when we bring people together, whether their injuries are seen or unseen, it unites us as people, and that’s an important connection to have.”

Movement, rhythm, and tempo are important aspects of music that can support cognitive, physical, and behavioral flexibility. Movement pairs well with music, particularly with the rhythmic element of music. Kristi explained, “A marching song may stimulate the movement without striking you that you are being influenced by the music. You may feel the marching rhythm and tempo in your bones even if you are not able to move to that rhythm, but you still feel that rhythm.” Kristi explained further that “… a faster tempo may be used for hand and arm movements because these movements require fewer muscles to move quickly. With the larger leg muscles, a slower regular beat may be preferable.”

Kristi explained that music might help people focus on a particular word or phrase in the lyrics or a musical phrase or motif that occurs repeatedly. In addition, fun games with music may facilitate attention or memory or even divided attention if participants are asked to listen for a certain cue versus a different cue.

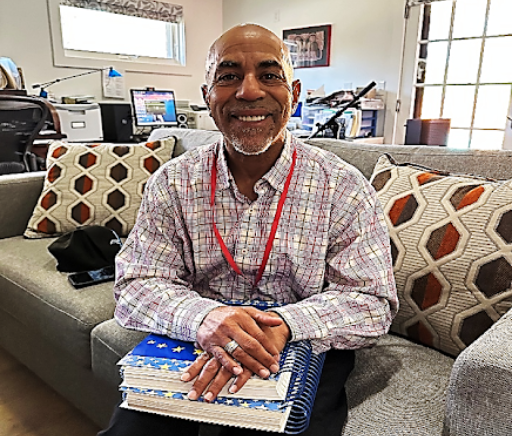

BIAC’s music and movement group members are encouraged to share their thoughts, feelings, and experiences with music. One man described himself as a semiprofessional musician before his injury, able to play several instruments well and compose music. Even though his specific skills were diminished, he said he was working hard to regain as many skills as possible, and he continued to revel in his involvement with music. An older gentleman told of being in London on a business trip prior to his injury and attending a Beatles (his favorite group) concert. He encountered Paul McCartney outside of the concert hall and obtained his autograph. That autograph and listening to the Beatles’ music still lifts his spirits and is one of the purest joys of his life. A particularly poignant story was shared by a woman whose injury resulted in retrograde amnesia. Although she remembers very little of her pre-injury life, often when she hears a familiar song, she experiences emotions attached to that song. She is starting, at least sometimes, to remember events and experiences associated with the song and the feelings it has evoked. In a very real sense, music has the power to heal.