Every Traumatic Brain Injury story is different, and the outcome for individuals is often unpredictable

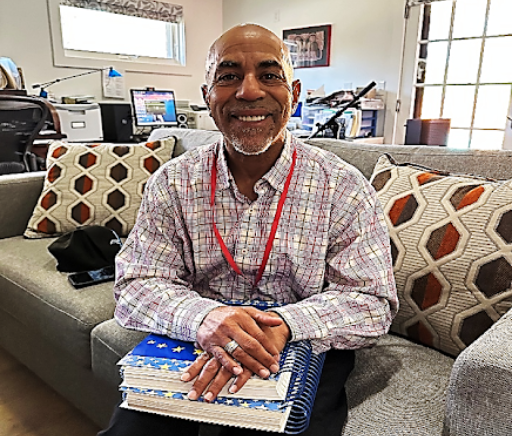

This is Sophia Augier's story

On February 26th, 2023, I glided over the freshly powdered slopes of Vermont as the flurries melted against my wind-burned cheeks. The twists and turns of the Rollercoaster Trail left me with an adrenaline high. Each jump I landed fed the thrill of the ride until I was suddenly consumed by darkness, and after the accident, my senior year turned into a nightmare. High school had gone exactly as planned. After years of hard work, late-night study sessions, and an activity-packed resume, I was set to attend the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the fall. My future was brighter than ever, but that single moment on the slopes left my future in jeopardy. Instead of celebrating my achievements, I was confined to a dark basement, stripped of social interaction, grappling with excruciating physical pain and overwhelming fear. Day after day, I sat there alone, trying to weed through the unknowns and search for a glimpse of hope. My dreams of MIT felt impossible as I struggled with memory loss, severe headaches, and an inability to read or even step outside.

As the days passed, the events of that fateful day slowly returned to me. The edge of my board clipped the snow so fast, sending me tumbling before I could react. When I regained consciousness, I was met with blood-stained snow through waves of darkness. Having lost control of my bladder, I found myself soaked to the bone and gasping for air as my face pressed against the snow. Despite this, I forced myself to get up and make it down the mountain. Embarrassed, I brushed off the incident and continued with my day. With the fresh snow the following morning, I ignored a nagging headache and returned to the slopes. It wasn't until the ride home that overwhelming nausea forced me to acknowledge something was wrong. Days later, my symptoms worsened, but they aligned with a typical flu rather than a traumatic brain injury. Initially misdiagnosed with mononucleosis by my physician, it took an emergency room visit to finally confirm my concussion. The unfortunate waiting period had consequently worsened my symptoms and prolonged my recovery. Finally, a specialist confirmed my worst fears. While the flu-like symptoms faded, my blurry vision, memory loss, and headaches persisted. The prospect of MIT seemed more distant than ever. Returning to school felt surreal; I could barely participate in classes. Watching my friends celebrate their college commitments, I felt like a kindergartner in a 12th-grader's body while I sat in a dimly lit corner, unsure if I'd ever think like myself again.

Months of vision therapy and rehabilitation followed. The drive and grit that fueled my academic success now drove my recovery. Slowly but surely, the darkness lifted, and I began to see a future again. My hard work paid off, and I regained the ability to pursue my dreams.

Today, I have just completed my first year at MIT. I joined the Division 1 crew team, worked for the MIT ambulance service and made lifelong friends. As I write this from my apartment in Cape Town, South Africa, where I'm conducting engineering research, I reflect on my journey.

My experience taught me that life's path is unpredictable. Adversity can strike at any moment, but it's how we respond that defines us. The pain and fear I endured were real, but they also revealed a resilience I didn't know I had. Embracing this resilience, I learned to navigate the unexpected and emerge into the strong woman I am today. In the grand scheme of life, our challenges are as much a part of our story as our achievements. My traumatic brain injury was a test of my strength and determination, and it reshaped my understanding of success. True success isn't just about reaching our goals; it's about finding the courage to keep going when those goals seem out of reach. My journey through concussion and recovery has been my greatest teacher, showing me that resilience, determination, and hope are the keys to navigating life's rollercoaster ride.

Sophia Augier